Diet culture sucks. Misogyny sucks. Systemic inequality sucks.

But what can the average person do about it? You’re making the first step, even if you didn’t know it, by simply subscribing to this newsletter (and, by extension, the podcast!). Because you can’t even know there is a problem unless you’re aware.

We’re serving up awareness here!

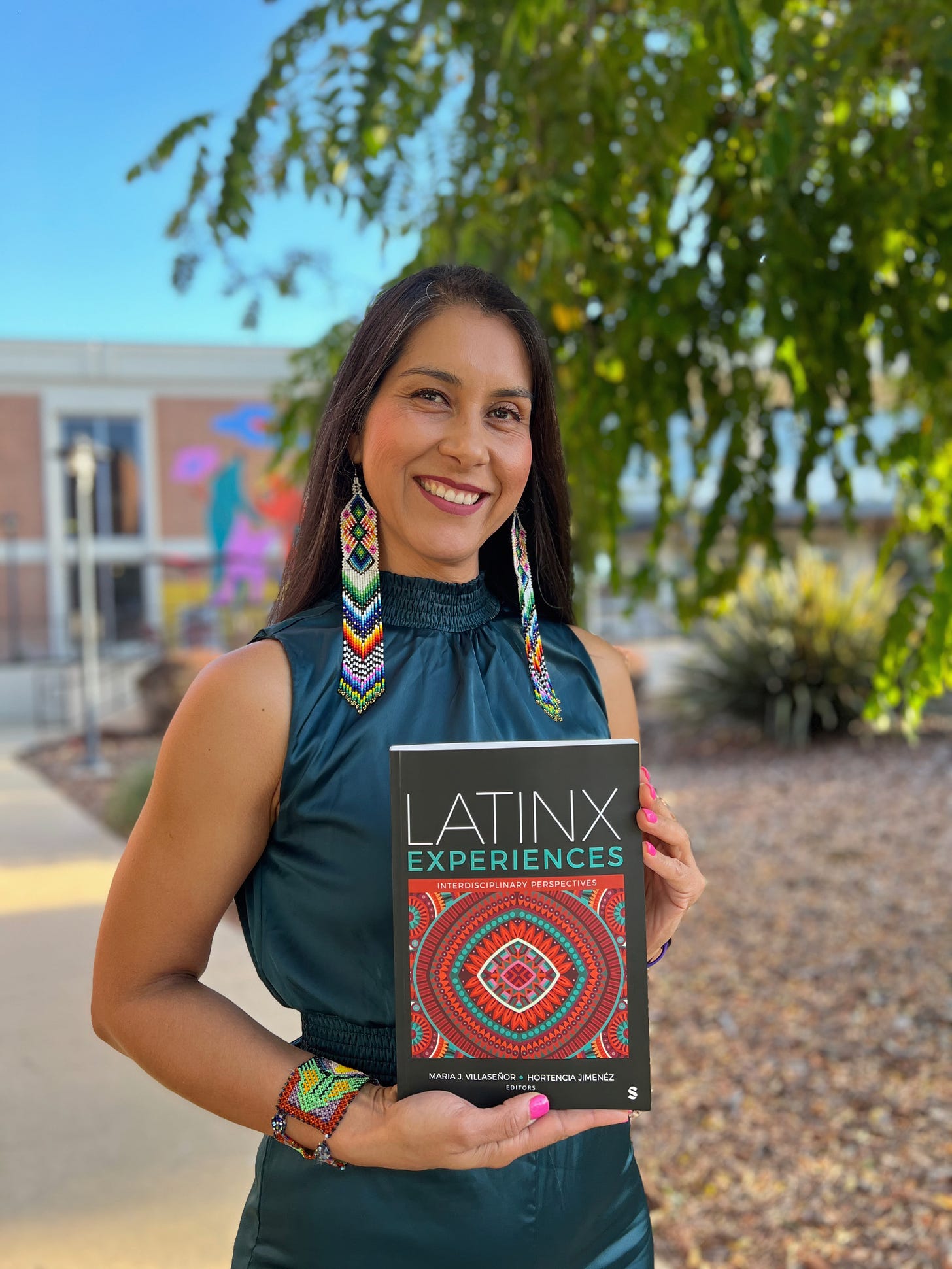

What follows is a fully translated and shortened version of the interview with the venerable Dr. Hortencia Jimenez, whose bio and background you can read about in the last post.

Dismantling Diet Culture with Dr. Hortencia Jimenéz

There’s lots of cussing in this one #SorryNotSorry🤭

Also, at the end of this conversation we talk about sharing our podcasts so that they’re visible. The algorithms keeps our voices buried under not only larger shows but also less contentious content. When you’re trying to change the system, the one that’s stacked against all of us—yes, that means YOU, too—they only way to do that is to amplify the work of the people on the front lines.

With that in mind, please share this post:

Paulette: I am talking to the one and only Doctora Hortencia Jimenez today, and I cannot tell y'all how excited I am. So, Doctora Jimenez, por favor, tell us, what is diet culture and why do we have to be so aware of this?

Hortencia: Thank you so much for inviting me on your podcast to be part of your community. I am very passionate about dismantling diet culture and not being silenced, right? Not being calladita (translation: quiet, silenced).

As a trained sociologist, professor, an author and researcher, as well as a health coach, the way that I conceptualize diet culture is as an industry that is rooted in systems of oppression in our society. And I invite folks to think about a spider web. A spider web has a lot of interrelated threads, right?

And so when I think about the diet culture industry, it's like a macro, like a huge industry. But it's made up of different institutions such as the family, the government, religion, the healthcare system, the fashion industry, the beauty industry, the media. So all these institutions enforce belief systems and values that oftentimes make us feel, and we are also, oppressed.

Diet culture is a system of oppression rooted in patriarchy, rooted in cis-heteronormativity that perpetuates a lot of the -isms in our society. And specifically, people think about diet culture as doing dieting. That's just one component. I see it very more broad and holistic.

It's more than just trying to conform to these Western ideals of body image, of thinness, of middle class, cisgender, which leaves out a whole diverse population, right? And so that's how I conceptualized diet culture.

Paulette: What I love about your podcast specifically is your tagline is, “fuck being calladita.” And that's so important because that is yet another system of oppression, taking away people's voice, taking away their power to speak. So when people talk about stepping into their power, what they're saying is they're finding their voice and they're giving themselves permission, liberating themselves from not being able to speak up.

And you provide that platform.

Hortencia: When you hear someone saying that, it's so powerful. And it's so liberating when we're able to tap and honor and embrace our voices and speak up when we have been conditioned and socialized all our life not to. And not take space.

So thank you for that validation and affirmation. It shouldn't be radica. But for many of our families, they remain silent and they want us to continue to follow the status quo. And not make noise, not cause trouble, no ser unas rebeldes (translation: don’t be rebellious), or the different labels that our family uses to try to silence and put us “in [our] place.”

Paulette: Putting a woman in her place has long been a sport for as long as men have been in power. And women, when they get themselves into power, it's that like proximity to power, proximity to whiteness. They tend to also then try to silence women behind them, don't they?

Hortencia: Absolutely. Yes. For folks who perhaps don't know and need a little bit of refresher, the way that I talk about systems of oppression, I want folks to think about it from a systematic macro lens.

And what I mean by that institutional and systematic, it's that it's embedded in the social institutions of our society. The systems of oppression have been at the foundation of the birth of this nation, that's how rooted systems of oppression are. And it's systematic. We're talking about not decades, but centuries of mistreatment, of exploitation, of abuse, of people of color, of BIPOC folks in the United States.

And that's one part, at the systemic macro level, which translates at the individual interpersonal level: how we internalize a lot of these belief systems that as an Indigenous woman, they were not ours, that was part of the colonizer. So we have colonized ideas that if we don't unlearn them, we're creating harm at the individual and interpersonal level.

So how do we do that? Institutions and individuals can perpetrate sexism, can perpetrate ableism, classism, ageism, antisemitism, nativism. And we can keep going. So when I talk about systems of oppression, that's what I refer to.

Paulette: So the decolonizing aspect of diet culture is removing those Western ideals, right?

Hortencia: Yes, yes, yes, it's unlearning them! Sometimes it's hard, right? We can't unlearn and dismantle something if we're not aware. That's the first step. People have questioned me and challenged me, which I welcome all that. Always when it comes from a place of intention. And they're like, “well, we really can’t dismantle diet culture because it's this, it's a system, it's an industry.”

I'm like, “yes, we can! I'm a sociologist. It all begins at the individual level. It all begins with you. It starts with you.” So yes, I sometimes feel like, am I making a difference? Estoy poniendo mi granito de arena (translation: it’s just a drop in the bucket, or, I’m just adding a little grain of sand), because sometimes it feels so big. But then I think it starts with one person. It's talking to your family, talking to the women in your life, to the men in your life, to the people in your life.

And the ideas and values that you have internalized for generations that were passed on from like three or four generations, they don't belong to us. And if we continue to hold on to some of these oppressive ideas and values, sometimes we lose ourself, we lose our sense of authenticity, our sense of identity for trying to conform to society and lo que quiere la familia (translation: what the family wants).

And that's why I like your podcast. You are dismantling diet culture because you're like, fuck, like, I don't want to have children. And there's so much shame that the family makes you feel guilty. Just because we're born with the vagina doesn't mean that, like, you're supposed to be a mother!

But again, these are ingrained ideas passed on from one generation to another. So the work that you are doing is dismantling diet culture because una mujer no tiene que ser madre nomás porque es una mujer, (translation: a woman doesn’t have to be a mother just because she’s a woman) right? Son ideas que se han pasado de la religión (translation: these are ideas that come from religion), plays a big role. So see how we're linking the family as an institution and religion?

And so these play a big role. So, I think that that's why I like the way that I conceptualize diet culture because it's very broad and very holistic, they're interrelated. We can't just say that it's just dieting, it's food. No, as people of color, of communities of color in the United States, it's all these systems and how they work together to marginalize us.

Paulette: As we've learned, sometimes it takes you being brave to stake your claim and be different, to not conform to what the family, what society, la iglesia (translation: the Church), religion, all of these things are telling us. And we feel like we're the ones who are wrong, whether it's that we aren't having kids or that we aren't a size double zero.

And there's been a shift too, because I remember in the 90s, for example, most of the people you saw on TV were not super skinny. They weren't little-little, they were like the size six was the ideal. And size six is still small, but it's not size two. It's not size zero. ¿Que pasó? (translation: what happened?)

What do you think has happened in the last 30 years that we just want women to be smaller and smaller and smaller?

Hortencia: Ooh, there's so much to unpack! We're talking about social constructs and social construction of the ideal body type. The idea that the size is going to determine your worth and beauty. And ultimately it does translate, for some folks, to access to resources and opportunities and that, for some, can translate into power.

That's one thing. The social construction of size, because who gets to decide that this is the size? What are the institutions? The media is an institution. Also, the fashion industry plays a big role. People can demand [better], that's why now we see that shift in health of every size and body diversity.

There's slowly a shift, very slow shift, where we can see more clothes for women in bigger bodies. But that was not the case in the past. Again, we're talking about the social construction of size and clothes and who has the power, who sets these trends? People in positions of power, and oftentimes it's white, cisgender women who are in straight sized bodies and heterosexual middle class or upper class white men.

Or if it's women of color, [they] tend to be also thin women as well. But, como dicen, ya basta no (translation: how do they say, enough already!)? People are fucking fed up that there's a lack of representation. And people are fucking dying. They're starving themselves to fit into size zero.

When they have a beautiful blueprint that's different and we're unique, but we've been conditioned to think that this is what we need to aim for. And the more time that you spend trying to conform and literally physically shrink by losing weight, we're not taking space. So we think about it physically, but metaphorically too. You're spending your time, your resources to shrink when you can spend your time and resources to feel empowered, to be brave and strong and be outspoken and take space and take these positions of leadership.

So I generally do think that diet culture flourishes by women shrinking, and not just women, straight, cisgender women, but folks in the LGBTQ community. If you're spending so much time doing that, you're depleted energetically. How are you going to do the fight for liberation? How are you going to advocate for others?

You don't, you lose yourself in that sense. So yes, you're shrinking for someone, but also you can be doing other important things in the community. But we've been gaslighted that we don't have power, that what we do doesn't create social change. And that's not true.

Paulette: So, we talked about the systems that are in place, we've talked about how everything's interconnected, there's a spider web, and at the center of it is these institutions that have made this systemic, that's the spider web, that's the system we live in.

How can I, as a little fly, trapped in the spiderweb, not get devoured? How does the individual find themselves and save themselves, really?

Hortencia: As a woman of indigenous ancestry and being proud of being from the Sierra Madre in the state of Nayarit, which is very high in the mountains, where they live off the land. It's very remote.

And I say this because I truly believe we've been gaslighted by diet culture and systems of oppression that we need to conform to society. That we “need to assimilate.” Which is not true. Now we do acculturate, but in the process of acculturating, some folks completely leave their heritage, their foods, their custom. That is what diet culture wants.

When we disconnect culturally and ancestrally, we are giving our power away. I share this because as an indigenous woman, and then my academic training, all this has helped me in my own healing. We can be the mosquita (translation: tiny fly), be really small, maybe feel that we're going to be devoured, I am calling folks to tap into their ancestry, to tap into their ancestral wealth and knowledge. We have that. It's in our DNA. We carry it right now in our bodies, but we've been disconnected because of colonialism, because of the violence that our ancestors had to survive.

But we have that power and that agency. Yeah, you might not know who your grandparents are, great grandparents, but can you do some research? Can you find out more information? Can you learn more about your cultural ancestor practices, your foods? It's the indigenous revival, a cultural revival.

You can do that, connect to the land, to Mother Earth. Religious, if you want, or spiritually. For me, that has been part of the healing. It has been my superpower. I don't want share this often with folks. My indigeneity, [the] re-indigenizing journey has saved my life coming out as a queer woman.

Tapping into that and connecting to my ancestors and their wisdom and the messages that they have for me, give me a deeper meaning. Y no me importa lo que diga la gente, lo que los demas van a decir, porque (translation: and I don’t care what people or anyone else will say, because) if you have a strong conviction and you have a mission and a vision that is beyond an ego, and that it's a deep calling, ancestral calling, and a community that is community-oriented, you're fucking powerful! But I didn't get here like de un dia para otro (translation: from one day to the next). It's been 20 years.

Honestly, the last seven years have been so painful.

So I stand here today strong and I feel fierce. I have my days where I feel like I'm so fierce and there's days where I feel so vulnerable and so scared. But then I go to my altar, I go and connect with my ancestors, I play my drum, I play my fruit, I burn some sage, I have my herbs in my garden.

Y me hago una limpia (translation: and I do a cleansing). I do ancestor practices. We've been gaslighted by white supremacy, que what the fuck is that? You're not supposed to, eso no funciona, eso es cosa del diablo dice la religión (translation: that doesn’t work, religions says it’s the work of the devil). But honestly when we're able to tap into that, I think we are grounded and have a deeper sense of our identities. And that's how I, that's how we, are able to do this work.

Because when you see it, you're like, “how am I going to get out of this spiderweb?” Porque no vas acer tu (translation: because it’s not only you). It's not just one person. That's part of individualism and rooted in white supremacy. I don't do it by myself. You're not doing this work on your own. We have community and community looks very different for folks.

We belong to different communities. So you're doing your own individual healing work and dismantling of internalized narratives, and you're also doing that in community. You're doing it with the support system or you find that support system and then that's how we're able to create that change in our communities. Like physically in our communities and our families.

People may think oh that sounds really nice. Well, I've been doing the work. This is possible. It's hard work. That's why folks don't want to do it. But social change begins at the individual level and it's collective and then systematic.

Paulette: I had a previous guest and we were talking about burnout, which again, is one of those colonized mindsets. And she was talking about how people stay in familiar pain because it's comfortable.

Hortencia: Oh yeah, and it's, it's comfortable and you're familiar with it. You're like, “how can feeling shitty be comfortable,” right? When we're able to catch ourselves, porque (translation: because) I go back and then I say to myself, “Hortencia, are you self sabotaging yourself?”

Are you feel shitty because you don't want to do that next step because that's fucking scary. So that's how I talk to myself. So yes, you're right. Nos quedamos esa zona de (translation: we stay in that zone) comfort, right? We say in the comfort zone and it's not a comfort zone. It's what we know. And it's part of our survival, right?

That's why we can do ancestral healing, which I invite folks and Western therapy too. I'm all about different modalities. I've had good therapists and awful therapists, and I've been shopping around for years looking for different ones.

Paulette: I've never had a great therapist. I did have a therapist on the program and she was very clear, “I'm not necessarily the therapist for you.” We talked about like, how do you break up with your therapist? And she's like, “just tell me, because if I'm not right for you, then I can open up space for the next person that I am right for. And you now have the time and energy to go find the proper person for you.”

And that's so important because therapy is, is an umbrella and there's so many different ways within Western medicine to approach it. There is a place for everyone within paradigm. You have to do the work. That's the hard part. And that right there, the hard part is why people stay in familiar discomfort. Because even though they're uncomfortable, changing that takes a lot.

And some people energetically aren't there yet. They don't have the energy. They're so piled on by society of all these expectations and all the stuff they literally have to do, and all the things that they think they have to do and all these expectations. Y todo esto (translation: and all that). I mean, no wonder people are so angry.

Hortencia: Yes, so unhappy. And the invitation is here, right? To embark on this journey of healing. And healing is as a non-linear life process. Así es (translation: that’s how it is). If at first it's hard and messy and difficult, you're like, wait, I'm supposed to feel better, but I feel more shitty.

Paulette: Yeah. It does tend to dip down first and then come up.

Hortencia: Yes. It goes up and down like a rollercoaster. So if you're listening and you're like, “hell no, I'm not ready” or “I don't want to do this.” That's okay. We're here, I'm here to hold space for that too. Divesting from diet culture is not causing harm. And who am I to say you should do this? You have your own divine timing, whenever that is. And whenever that happens, that's time.

You just gotta be compassionate. Again, I always bring compassion in every interview and even on my own podcast. No, enserio (translation: seriously). If you ask me, “what is a secret sauce or a strategy you have?” Ah, compassion, self-compassion.

Paulette: And that's key because if we're not nice to ourselves, who's going to be? These are all things you can learn to do. They take time. And they take effort.

Hortencia: It's a practice. We're here genuinely telling you the truth. That is one of the big strategies in addition to therapy, in addition to movement that you enjoy outdoor, in addition to connections and relationships, that's part of your mental health.

It's really being aware of these thoughts and where do they come from and how have they harmed you and how do they not allow you to continue to show up or limit you? What are the limiting beliefs that you have about yourself? And when we're able to identify them. That's where the work begins, because that's where our growth is.

Every time that we grow professionally or personally, these limiting thoughts will come up. And it's scary. I still struggle when I have opportunities or goals that I have put forth and then the universe blesses me with them and in the right divine timing, then I'm so scared.

I'm like, “Oh my God, I am freaking scared. Can't believe this is happening!” And then the self-sabotaging comes in and then the way that I talk to myself. I'm here telling you, I still struggle with this. Digo (translation: I say to myself), who are you to dream this big?

A lot of our growth comes with reframing these belief systems and creating new ones. Because once we create those new ones and we repeat them to ourselves, we can go for that goal. And keep going and keep growing.

Paulette: Growth is what we're looking for. And growth looks a lot of different ways to different people. But even as you're growing, as you're breaking down all these walls and barriers in your own mind, you'll find new ones. This is almost a constant thing. And like Dra. Jiménez just said, those fears will still bubble up until you deal with them. But new opportunities, new environments bring new fears. But they're the same old theme.

Hortencia: Yes, it's the same fucking theme and I say fucking theme porque I am so exhausted of the same narrative that keeps popping up for me. And I'm allowing it too, because it's easy to stay in that narrative, because it's also safe. It doesn't require you to grow. It doesn't require you to have the courage to take that step.

So, I'm all about embrac[ing] that fear. Agarra a el miedo por los cuernos (translation: grab the fear by the horns), get the bull by its horns and go for it. Even though you're scared as hell, reach out to a support system to cheer you, to send you those messages, you got this. That's what I do.

I'm crying. I feel like I'm going to faint. And, and then I do it and then I'm like, “I did that, I did that!”

Paulette: I find it interesting that so many of us women later in life, now is the awakening for us. And I really, really wish I'd had this 20 years ago. But I didn't have the life experience 20 years ago to even see this clearly. So [if] the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the next best time is today. So if you're hearing this today, and if you're of a certain age, even if you're not, if you are 25 listening to this, realize that the change can start today.

The first step is recognizing that you have to do it. And then the second step is to keep going because it's scary. And if you're the first, for example, childfree person in your family, you had no other models of how to be childfree. What does that look like then? Then you go find the community where you're not the only one. You go lean on the people who will support you regardless.

I'm thinking about myself at 46 and how, man, I really wish I'd found my voice earlier. I really wish I'd found my superpower, the thing that I'm good at. But all of that had to be revealed when I was ready.

You might not want to sit in that discomfort anymore. You might really think that you're ready. You find out as soon as you start taking the step, right? You start breaking away from that spider web and breaking out of your comfort zone.

And yeah, fear is natural. It's one of those ancient sensations we would have in order to keep us safe. The flight or fight response and now it's grown as we've evolved as humans. There's fight, flight, fawn and freeze. A lot of people freeze up when they're in fear and they want to run away from the thing.

But the truth of the matter is that the things that scare us are mostly expectations coming from outside. Because there's no real saber tooth tiger hiding in the grass looking to attack us. That doesn't really exist anymore. Or whatever the modern equivalent is of someone who's going to eat us if we step outside of our comfort zone.

How have you dealt with that?

Hortencia: Before I answer the question, I just want to tell you that I completely relate to what you shared about, like, why didn't this happen 20 years ago? I would say that in the last 10 years, 7 years more specifically, I would question. And I would be upset and I would even tell my therapist, “why now? Why couldn't I do this? Why is it happening now? Not in the past.”

[Because] I was not compassionate and that was really harming me. And she's like, this, “this is your time.” I want folks to know, cause that in itself is hard when you, you're beating yourself up for like, why didn't I do this work 20 years ago or 15 years ago?

Porque tenias que pasar por todas esas experiencias, because you had to go through those experiences. And they didn't really hit me until last year. I just created a new course called Latina Sexualities. I had this course in mind for years and I wasn't ready. Intellectually, I had it. But personally, I was struggling, and I could not get to this course, and to create it in my community college, until I did the healing that I needed to do.

And I did it and then I created this course. If I would have created this course five years ago versus now, I would It would be very different because it's my lived experiences that I'm putting into this. So that's an invitation for folks too, [it’s] divine timing.

Las cosas en su momento (translation: everything in its own time), and don't think about like, “oh, what if in the past?” Because that only makes it worse, and that also hampers your own healing.

So now to answer your question, how have I done my healing? Like you said, being the first. If you're the first in your family to be childfree, that's fucking scary to say, like, “I'm not going to have children.” ¿Y por qué, que va decir la familia? (translation: what will my family say?) But you had the courage to say, “this is the life that I want for me.”

Healing is courage. Courage to unlearn, to heal, but also to find yourself and your authentic self. Because we're constantly changing and evolving our sense of ourself. Sometimes we tie our social identities, identity or identities, to particular people. And if we may lose them or if relationships end, then you're like, “who am I?”

So for me, it has been a courageous act. It has been beautiful, it has been messy, it has been painful, and it has been a rebirthing of Hortencia. Who I am right now in 2024, it's very different who I was in 2014. Huge, huge.

And I think my family, my community, I believe in God, I don't believe in the institution of religion, but I do believe in God and I believe in my ancestors and the creator and the spirit. So all that and Western therapy has been part of my healing. And we didn't talk about it too much, but food. I love food!

So connecting to my traditional culture foods, oh, eso me da vida, me da amor (translation: it gives me life, and love). It gives me pleasure and joy and see, happiness!

Paulette: Yeah, your face lights up as soon as you start talking about it. So we're going to talk about it more.

I found a Google question and this disappointed me because this is what happens when all of this data is scraped by Western-ers, the Western culture. “Is traditional Mexican food a healthy diet?”

¡Claro que si! (translation: of course it is!)

Hortencia: Claro que si. Caveat here, I'm a health coach, but I am not a nutritionist or dietitian. So I can speak as a health coach and sociologist. As Dalina Soto from Your Latina Nutritionist talks about, health is how we as individuals have our own definition of what health is. But our culture foods have historically been demonized, and that's research that I've done as a sociologist and a chapter that I have in my own book. Westerners and the dietitians of the 1800 and early 1900s, they racialized the way that they talked about culture foods.

But this goes back with the colonizers when they came to the Americas, how they vilified our culture foods. That's where it comes from. So we're talking about generations and centuries of demonizing traditional culture foods. I'm telling you as a sociologist. So here we are right now in 2024, where que las tortillas son malas, que el plátano frito, que las comidas tradicionales son malas. El racismo es malo, la homofobia es mala. La discriminación por ser imigrante mala (translation: tortillas are bad, fried plantains are bad, traditional food is bad. Racism, homophobia, those are bad. Discriminating against immigrants, that’s bad.).

Racism kills people. Microaggressions have a toll on your mental health. Why aren't we talking about that [instead]? That has a more impact than eating canned food. So, that's the nuances that are missing in the wellness industry. You can “eat healthy” and eating healthy is white middle class ideas that they healthify our culture foods, which I find extremely offensive.

Not only are they healthifying our foods, but they're also culturally appropriating our foods. Or "discovering" our culture of foods. So that's part of the wellness [industry] and it's connected to diet culture. And like I said, I'm not a nutritionist. I can't tell you all the nutrients that our culture of foods have, porque that's not my training and it would be a disservice if I tell you, la tortilla tiene esto (translation: tortillas have this nurtrition), no?

Yo sé que tiene fibra. Yo sé que los frijoles tienen proteína y fibra y otras cuantas cosas. Pero (translation: I know tortillas have fiber, and that beans have protein and fiber and other nutrients. But) that's what my ancestors ate. I eat conventional, I eat processed packaged food, canned food, frozen food, homemade food, whatever is accessible for me and depending on my time.

And we should not feel guilty because that's what some folks may want. One, to make you feel guilty for eating a certain foods, but what are your resources? What's your budget? What's happening at home?

And sometimes we make certain compromises. So people need to stop shaming folks for what they're eating. And they need to stop shaming our culture foods because our culture foods are rich in culture, rich in love, in the traditions, las platicas (translation: the chit chat), the conversations that happen in the kitchen.

That is all part of our traditional culture foods in addition to all the nutrients that they offer.

Paulette: Our culture as Americanos and along the Americas, but also here in the U.S., they will extract as much money out of a superfood, once it's “discovered. Quinoa, for example. We all know quinoa has a higher amount of protein than white rice.

But once that was discovered, suddenly we can make money off of it. And then the rippling effect for the indigenous people who have eaten this their entire lives, suddenly it skyrockets in price and it's taken away from them. So when you're talking about cultural appropriation, that's what sticks with me. That's what pisses me off.

Hortencia: Claro que si, that's how it is. How do I even like begin to unpack this?

And I won't be able to in this episode. But I want folks to understand that when we're talking about diet culture and systems of oppression, when we're talking about food, an area that people don't talk about in the wellness and in the undieting space, which is where I'm at, is the food system. How the impact of the food supply chain, the environment, some sustainability, and how we are degrading our environment and Mother Earth, all this is connected.

How food is produced, how workers are exploited. There's human rights abuses. There's human trafficking. There's people working in restaurants. Hay gente que esta aquí (there’s people here) [through] modern slavery, human trafficking. So all this is connected to systems of oppression. Food is connected to the food supply chain. And also to the different forms of inequality that workers are experiencing.

Paulette: And all too often, shaming around food starts really young. Really young, because kids are not taught that there's more than what they eat at home. I was just watching a show where Alex Guarnaschelli, she's a white woman who grew up here in the US. One of the chefs was Asian and he was made fun of growing up because one, he had a funny name and two, he ate traditional Asian food for lunch. Kids would make fun of him because it was stinky, because it was different.

And she, [Alex] was nearly in tears talking about how she experienced something similar. Because the Italian food her mother would send her to school with was also so different from what the rest of her classmates were eating, she would eat it in the bathroom.

So this isn't just happening to little brown kids, poor little brown kids. This is just happening. And parents need to do better. You need to do better with your kids and teach them about diversity so that this stuff doesn't happen in childhood.

So that we grow up being welcoming of stinky food as opposed to shutting it down and making fun of people. And then that leads to bullying. And that's a whole ‘nother systemic problem. Everything is so interconnected!

Hortencia: Yes everything is interconnected and it's difficult. I get to answer when other Latinas reach out, ¿como le hago? (translation: how do I do it?) How do I talk to my mom with the food and body shaming, but I live at home. Generally, they're asking me for like advice or direction and it really just breaks my heart when you're trying to make changes, when you're trying to unlearn. And you live in that toxicity at home, and you don't have a lot of freedom and liberty.

That is definitely a challenge, and the boundaries are important. When we're talking about food shaming, calling it out, disrupting it. But again, it's all about “how's my mental health? Do I have the capacity? Do I have the energy to engage with this family member or all this other person? Do I just brush it off? Do I ignore it? Do I say a joke?”

There's different strategies. You'll use different strategies with different people or just depending on the context, depending on your energy. So that's an invitation also for folks that you don't have to put up with this shit. You can set a boundary and be respectful, especially with our elders. I will call them out in a loving, compassionate way or “don't say this because I have kids. Don't say this to my kids, I would appreciate [it].” Or prep them before they see the kids. It's a lot of emotional labor involved.

Do you have the capacity to engage in that emotional labor with loved ones who you think will respect you? And respect your decision, and perhaps it may even change. And there's some elders que nunca van a cambiar, se van a sentir ofendidos (translation: that are never going to change, they’re going to get offended), they're going to feel offended. And you're like, well, why not do this battle with this family member.

So pick your battles, but know that you have the power and agency to set a boundary, and boundaries are going to look different for different people in your life.

Paulette: It's unfortunate. We barely even touched on the body shaming and the food shaming. This is just another one of those toxic cultural norms we take for granted, that we call people flaca or gordo (translation: skinny or fat). Those are nicknames. They are treated as terms of affection. But they're also causing harm, and we really need to examine that as a society. As the older generation gets older and it starts dying off, no, it's not going to go away because it's been passed down.

So if you're still hearing it, it's on us to say, ya! Ya basta (translation: enough, stop!).

Hortencia: Ya basta. Yes, ya basta. Shamelessly plugging in here, I have a free resource, a free ebook on how to set boundaries on food and body shaming. It comes from a culturally relevant lens. So download the resource and see what you can get from there that can be helpful.

And I'll be more than happy to come back and talk more about this because it's so ingrained in our families. The food and body shaming, that we, some folks don't even question it. At all. Or dicen, oh, es que si son las cosas, that's how things are, but it affects your mental health.

Paulette: Dra. Jimenez, is there anything else we should know about you or anything else that you would like to promote?

Hortencia: Pues (translation: well), support my work on Instagram, download my free resource. And then the last is my podcast, Dismantling Diet Culture, Fuck Being Calladita.

And you can support the podcast by listening to it, leaving a review. And also, of course, leave a review here in La Vida Más Chévere también (translation: also).

People think, “why?” Because representation matters. When we get your review, when we get that star, that gives us visibility because our voices are muted. They're muted by other, bigger podcasts that tend to not present the communities that we come from. That's why we're always saying, please leave a review. Please follow the podcast, please share it. Tell a friend.

Paulette: Si (translation: yes), that's what allows us to grow. But that's also how you start helping other people have that reframe, that mental shift, that allows them to let go of those toxic cultural norms. That's how it starts. Just by sharing, sharing this episode. Sharing Dra. Jimenez's episodes as well.

Hortencia: That's a burrito!

How to Listen to Dismantling Diet Culture with Dr. Hortencia Jimenéz

Listen to Dismantling Diet Culture with Dr. Hortencia Jimenéz on your favorite podcasting app or on Apple:

Like this post? Support this show and publication by sharing with a friend

or by: